Gail Smith walks into the vast recreation room at Franklin Wright Settlements’ (FWS) Youthville location and slowly turns around to take in the space. She has dressed up for her first visit to the place that changed her life — her leopard print booties and beaded headwrap belying both her age and recent circumstances.

Just months ago, the 70-year-old Detroit resident struggled to find food, surviving on a daily ration of peanut butter and jelly thinly spread on saltine crackers.

When asked if she frequently went to bed hungry, she exclaims, “Hungry?”

“No baby,” she says, the smile draining from her face. “I went to bed starving.”

In our region, Gail’s story is far from unusual and growing more common due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. Before the current crisis, 44 percent of households already struggled to afford their basic needs. Record-breaking job loss, school closings and economic pressure have further destabilized these households and created an unprecedented demand for food.

In 2018, food insecurity in Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties averaged just over 13 percent. This year, it is expected to soar to nearly 20 percent, according to projections from Feeding America, a leading national nonprofit food bank network.

As part of United Way for Southeastern Michigan’s effort to create stable households where children can thrive, we provide support to emergency food programs and lead collaborative efforts that build toward long-term food security.

In 2020, we distributed $3 million in basic needs grants, many of which supported food security. Since March, our COVID-19 Community Response Fund has awarded 187 additional grants totaling more than $13 million to support the food needs of thousands of families across the region.

A DESPERATE CALL

Gail, a native Detroiter who grew up on the city’s east side, says she has always been fiercely independent and reluctant to ask for help.

Like many heads of ALICE (Asset Limited Income Constrained, Employed) households, the mother of three grew accustomed to “just getting by” with little to no money for savings. Now that her children are adults and she is reliant on Social Security income, saving for a rainy day remains an elusive goal. After paying rent at her subsidized senior apartment each month, there is little money left for food. She buys only what she can afford, which very rarely includes fresh fruits and vegetables.

In March, the uncertainty of the brewing pandemic and announcement of stay-at-home orders left many store shelves empty and led to higher prices on the food that was left in stock. Like many Detroit residents, Gail lives in one of 19 neighborhoods labeled as a “food desert” — a term the Michigan Department of Agriculture uses to describe an urban area that lacks access to quality, affordable food.

Residents in these areas who lack reliable transportation often resort to purchasing food at convenience stores or settle for unhealthy, fast-food chain options that can exacerbate chronic conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure.

When Gail saw an FWS flyer outlining the organization’s senior food delivery program, she sat down on her sofa to make a call she never imagined having to make.

“I had to do something or else I wasn’t going to survive,” Gail says.

Health and hope

On the other end of the line was FWS COO Stacie Robinson, who handles calls to the organization’s emergency hotline that was added with a grant from Saving Our Selves: A BET COVID-19 Relief Effort fundraiser held in April in support of United Way chapters across the country.

One of the supporting organizations was United Way for Southeastern Michigan, which serves the city of Detroit, where the African American population has been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. Of the 9,464 COVID-19 deaths in Michigan as of Nov. 30, 32 percent were Black or African American.

“When she told me she had been eating peanut butter and crackers for weeks I knew we had to get her a food box immediately,” Stacie said. “At her age, it couldn’t wait.”

Gail’s sense of relief and excitement is still palpable even months later as she talks about receiving her first food box, which included chicken breasts, broccoli and oranges.

“It was heaven,” she said. “I couldn’t believe the amount of food that was in there.”

The grant funding from United Way has allowed the organization to meet the evolving needs of the community by serving more seniors in their homes.

Now, Gail receives weekly deliveries of nutritious food directly to her door. Since she first made the call to Stacie, the two have become inseparable, and her apartment building has become a drop-off location where other residents can also access healthy food without the risk of being exposed to coronavirus.

“You work hard all your life. You raise kids. Then you get to this age and realize there’s no help,” Gail said. “It’s a lonely world out here for seniors.”

Not the life she imagined

Gail got her first job at the age of 11 and worked multiple jobs for as long as she can remember — often turning to temporary agencies to earn extra money to make ends meet.

“You work hard all your life. You raise kids. Then you get to this age and realize there’s no help,” Gail said. “It’s a lonely world out here for seniors.”

One in 12 seniors don’t have access to enough food to eat, according to data from Feeding America. As the population ages, that number is expected to grow.

Gail spends most of her time in her apartment — some days staying up through the night because she doesn’t feel safe alone. COVID-19 has furthered her sense of isolation.

The relationship she has built with the team at FWS is a bright spot. Stacie says Gail is now like a grandmother to her. “It’s really special,” she added.

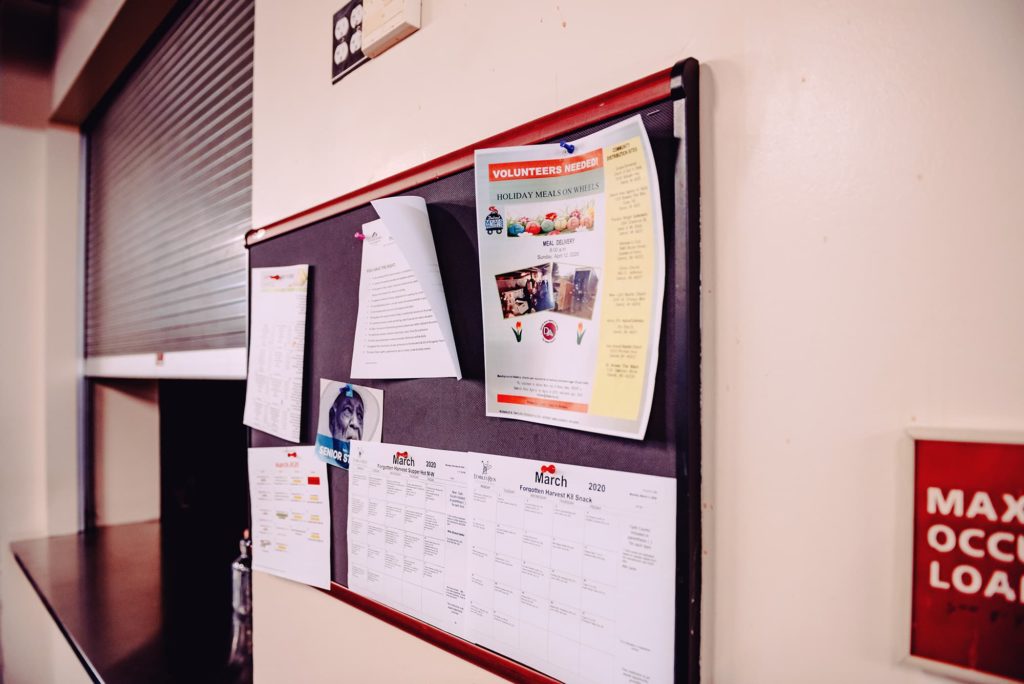

FWS offers a variety of senior programs, which will resume once it is safe to do so. For now, the activity calendar remains frozen in time, reflecting the flurry of events that last happened in March. Gail looks around the recreation room as Stacie describes the activities that take place there — weekly lunch and fellowship, jewelry making, movies, and more. Her eyes light up when Stacie mentions future bus trips to Walmart.

Surging demand

FWS typically serves an average of 570 people each day, including many of the community’s most vulnerable seniors. Since the onset of the pandemic, that number has nearly doubled and continues to rise.

Days before Thanksgiving, Stacie arrived at the building and was shocked by the line for food boxes, which extended for blocks.

“It scared me,” she said.

Many households that are food insecure do not qualify for federal nutrition programs and rely heavily on local food banks and other hunger relief organizations for support.

Sara Gold, Senior Director, Health and Basic Needs at United Way for Southeastern Michigan, says that after a period of small recoveries with many people returning to work, surging rates of COVID-19 have prompted new restrictions that will make the winter more difficult for many.

“In March, it felt like more of a sprint,” said Sara. “Now we understand it’s more of a marathon.”

As local families find both their savings and their pantries drying up, United Way is working with partners to build on the innovative programs developed in response to the current crisis and continuing to advocate for additional federal assistance.

Our 2-1-1 helpline continues to serve as a go-to service for people looking for help and information. Calls are answered 24 hours per day, 7 days a week to assist with unemployment claims, accessing food or housing support, or connecting people to volunteer opportunities. In March of 2019, our 2-1-1 team handled 9,162 calls. During the same period this year, the number of contacts more than doubled to 19,000.

Since then, calls have remained high, with more than 86,000 connections to services made this year. Referrals to food pantries remain a top request.

“The entirety of the food system is in limbo right now,” said Sara. “We’re living with a lot of unknowns and it’s going to take all of our partners and community support to find creative solutions. Moving forward, as we work through what will likely be the toughest months of this pandemic, we will need to be mindful of what it means for our communities to be truly resilient and work towards that as a goal.”