Across the country, historic and ongoing displacement, exclusion and segregation continue to prevent people of color from obtaining and retaining their own homes and accessing safe, affordable housing. Today’s email focuses on the impact of gentrification and how low-income groups, especially Black people, are at risk of displacement by this process of regeneration.

Gentrification is the process whereby the character of an urban area is changed by wealthier people moving in, improving housing, and attracting new businesses, typically displacing current inhabitants in the process. An effect of gentrification is the high cost of rents that force low-income households to move to lower-cost neighborhoods or even push them outside the city, with fewer resources. Gentrification can lead to different types of displacement.

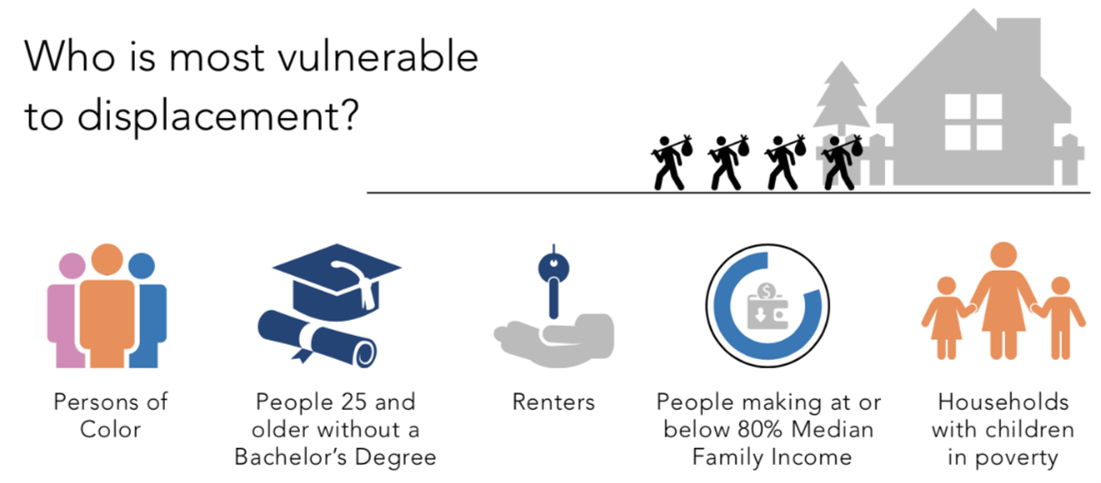

Displacement is the forced or involuntary relocation of residents from their neighborhoods or homes due to changing social, socioeconomic and political landscapes in their neighborhood. . There is direct displacement happening through rising housing costs, but residents may also be forced out by lease non-renewals, evictions or eminent domain. Indirect displacement happens through preventing new people from moving into the area, due to the high housing costs or because of discriminatory policies like banning tenants with housing vouchers.

Cities in Michigan, like Detroit and Ann Arbor, are heavily feeling the impact of gentrification. Detroit has seen one of the highest rent rises in the country in the last few years, while being one of the poorest cities. Since 2017, the average rent in Detroit increased a staggering 46.2%. Displaced low-income, often African American and senior households most likely end up in new low-income neighborhoods fueling further segregation. Displacement has harsh consequences for individuals as it can lead to disruption of (mental) health, employment and children’s education as people get removed from their work, school and health care. In some cases, it might even lead to homelessness if no alternative housing is available, or the costs of moving are too high. It can also lead to tearing apart communities and breaking down social networks and cultural identity, through the loss of neighbors, churches, and small businesses.

For example, while Detroit’s white, Hispanic and Asian population has grown since 2010, Black people now account for 77.2 percent of the city’s overall population, compared to 82.2 percent in 2010. And the impact often has spillover effects on surrounding cities, feeling the pressure of rising rents and risk of displacement.

In addition to housing, gentrification is impacting land ownership and farming. Black farmers, and Black-owned farmland, are at a historical low. In the 1910s, Black farmers made up 15 percent of all farmers, compared to just over 1 percent today. In Michigan, there are only 354 Black farmers, making up only 0.4 percent of all farmers in the state. Furthermore, Black farmers experience the lowest approval rate for USDA direct loans. Systemic racial discrimination is at the foundation of the barriers faced by Black farmers.

Displacement from homes, land, farms, businesses and communities all are propelled by gentrification. This is often fueled by tax incentives to wealthy developers to invest in the “regeneration” of neighborhoods and inequitable policies like discriminatory lending and redlining, where creditworthy and eligible people might be denied a loan for certain neighborhoods. Review Day 16 on Housing from the 2023 Equity Challenge to learn more about some of these policies and practices.

As you go through today’s resources, we encourage you to notice effective strategies and policies that promote equitable development and prevent further displacement and land loss.

Today's Challenge

Read

- Read about the negative impact of gentrification in Detroit: Rising costs and gentrification force locals out of Detroit’s downtown and Midtown. (15 minutes)

- Review these promising solutions at the state and local policy level to mitigate negative effects of gentrification: Localized Anti-Displacement Policies: Combatting Gentrification and Lack of Affordable Housing. (15 minutes)

- Read about Black Farmers in Ypsilanti and the barriers they face: Migration, gentrification & resilience: Ypsilanti gardeners share their stories. (10 minutes)

Watch

- Watch these two videos from the Urban Displacement Project to learn about displacement and gentrification Want to Understand Displacement and Gentrification? Watch These Videos. (5 minutes and 7 minutes)

Engage

- Learn about and engage with our Racial Equity Fund Partner, Detroit Black Farmer Fund, and the Washtenaw County Black Farmers fund.

Reflect And Share

- Think about where you live. How did your neighborhood change in the last decades and what impact does that have on the community and its people?

- How do you feel about gentrification? How has that changed after reviewing today’s email?

- How can positive change happen in neighborhoods without doing harm to current residents? Who should be included?